MSB History

Earliest Days

Prior to 1847 the State of Missouri made no provision for the education of blind citizens. In that year the legislature authorized $80 per year for the education of indigent blind youth. With a lifetime cap of $160 per person, this was enough for two years of schooling. In addition the total sum appropriated for blind education was $1,200 per year – which would educate a total of 15 blind pupils! In early 1851 the Missouri legislature appointed a committee to inquire into the feasibility of educating blind children. The committee considered educating the blind at the institution for the “deaf and dumb,” which was established that year. Meanwhile private citizens had taken the matter into their own hands.

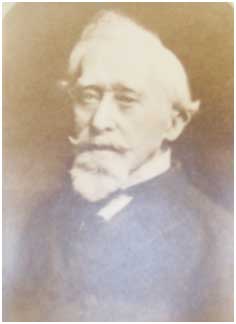

Meanwhile, Mr. Eli William Whelan arrived in St. Louis in fall 1850. Mr. Whelan was a blind man and former superintendent of Tennessee Institution for the Blind. He arrived with letters of introduction to several prominent citizens, including Dr. Simon Pollak, an ophthalmologist (pictured below). Mr. Whelan and Dr. Pollak formed an association of 20 clergymen and philanthropists. Together, they planned to found a charitable institution and apply for state support when they had established their credentials. This approach succeeded in 11 states, beginning with the 1830 establishment of New England Asylum for the Blind in Boston. It was followed within ten years by schools in New York, Philadelphia, Ohio and Virginia. During the 1840s, school. were founded in Kentucky, Tennessee, Indiana, Illinois, Mississippi and Wisconsin.

Mr. Whelan accepted his first pupils – 14-year-old Elizabeth Taylor from St. Louis and seven-year-old Daniel Wilkinson from Cape Girardeau. Mr. Whelan taught these two students for several weeks in his boarding house in downtown St. Louis. He then took them to Jefferson City to demonstrate their progress and ask for state aid. Success was not a foregone conclusion as the legislature had recently expressed the following opinion of education for the blind:

"There are only a few blind persons in Missouri, the United States census reports to the contrary notwithstanding. It would be time, labor and money lost to try to teach the blind to read or do anything else."

Both Elizabeth and Daniel were talented intellectually and musically. Their accomplishments persuaded the legislature to authorize the founding of “The Missouri Institution for the Education of the Blind.” The school’s inaugural date was February 27, 1851. Additionally, the state granted the school $3,000 per year for five years on condition that its founders raise $10,000 privately.

After several months and additional student exhibitions, the founders raised the $10,000. Missouri Institution for the Education of the Blind opened on November 1, 1851. The school remained a privately-controlled endeavor for several years until its founders determined they could not continue to support it. In 1855 the school came under the control of the Missouri state legislature. Over the next 160 years, MSB was under the supervision of various state department. These included both the State Board of Guardians and the State Board of Charities and Corrections. Since 1921, it has been operated by the Missouri Department of Education.

As the school grew it needed ever-larger quarters. In 1856 it moved into its own building at 20th and Morgan (now Delmar) in downtown St. Louis. The building had been purchased for $27,000 and, after enlargement and remodeling, would be able to house 100 pupils. By 1870, however, enrollment reached 125 and the school had outgrown these accommodations. The school then received $50,000 from the state to add two wings that tripled the size of the space. For students, the four-story building provided classrooms, dormitories, boys’ and girls’ infirmaries, music practice rooms and a gymnasium. Additionally, there were offices, staff quarters, bakeries, coal and vegetable cellars, piano tuning and repair rooms, and a seamstresses’ room. The building was heated with steam, lighted by gas and boasted hot and cold running water.

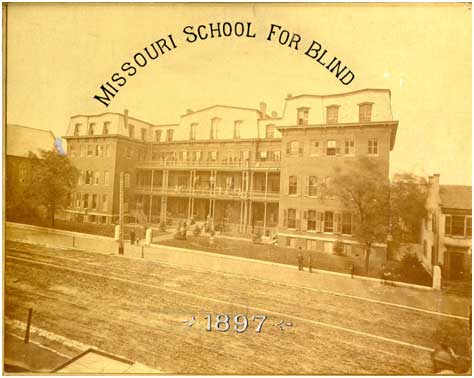

After years of deliberation, the Missouri Legislature agreed to sell the school property and buy or build a new facility. $150,000 was appropriated to purchase up to three acres of land. They selected the current site across from Tower Grove Park; the open space would offer students a place to exercise. It was in a quiet, safe residential neighborhood but only a block from public transportation. The school moved into its new red-brick quarters in September, 1906 (see photo below).

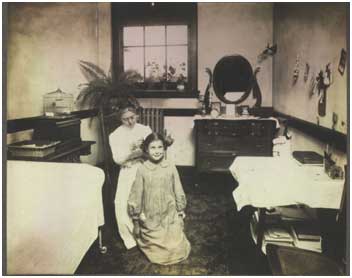

The state’s appropriation was insufficient to complete the entire building as planned so it was quite overcrowded. Dorms built for 12 students instead held 18, while pianos and music practice were crammed into dormitories or classrooms. Eventually, in 1912, one of the two needed wings was added, but the second was not built until the late 1950’s. For the first 25 years of the school’s existence all teachers were required to live at the school. Beginning in 1879, this rule was changed and only the superintendent and matron (housekeeper/ supervisor) were required to live on campus. Other staff could do so if desired, which many did. The superintendent resided on campus until the late 1990’s. Besides the superintendent, principals and teachers, the school employed housemothers (see photo below) for each dormitory. Their duties included:

"Giving the pupils such care as a mother gives, being with them at times as they are not in class. Training them in manners and neatness, and giving attention that pupils in a large institution usually fail to receive."

Such attention was important as students stayed at school for months at a time, going home only for summer vacation.